THE NIGHT PAIN TURNED INTO POETRY

The winter of 1950 didn’t come softly. It crept through the cracks of a Nashville hospital window, carrying the kind of chill that seeps into the bones — and the heart. Inside that dimly lit room, Hank Williams lay still, staring at the ceiling as the fluorescent light hummed above him. His body hurt. His spirit, even more.

Audrey had been there earlier. Her perfume still lingered — sharp, sweet, and haunting — a scent that used to mean love but now only reminded him of distance. Their marriage had been a storm for years: part lightning, part silence. That night, her words cut deeper than any doctor’s needle. When she finally left, closing the door behind her, Hank turned to his friend and whispered, “She’s got a cold, cold heart.”

Most men would’ve just sat there, drowning in regret. But Hank wasn’t most men. Pain was his language, and music was his way of speaking it. He reached for his guitar, the wood cool under his fingers, and began to strum — softly at first, then steady, like the rhythm of a confession.

The song poured out of him — no editing, no pretending, just raw truth in melody form. When he carried “Cold, Cold Heart” to the Acuff-Rose office the next morning, the men in suits hesitated. “Too sad,” one of them said. “Too personal.” Hank just smiled, that slow Alabama grin that could disarm anyone, and replied, “If a man ain’t never been hurt, he won’t understand it — but the rest of ’em will.”

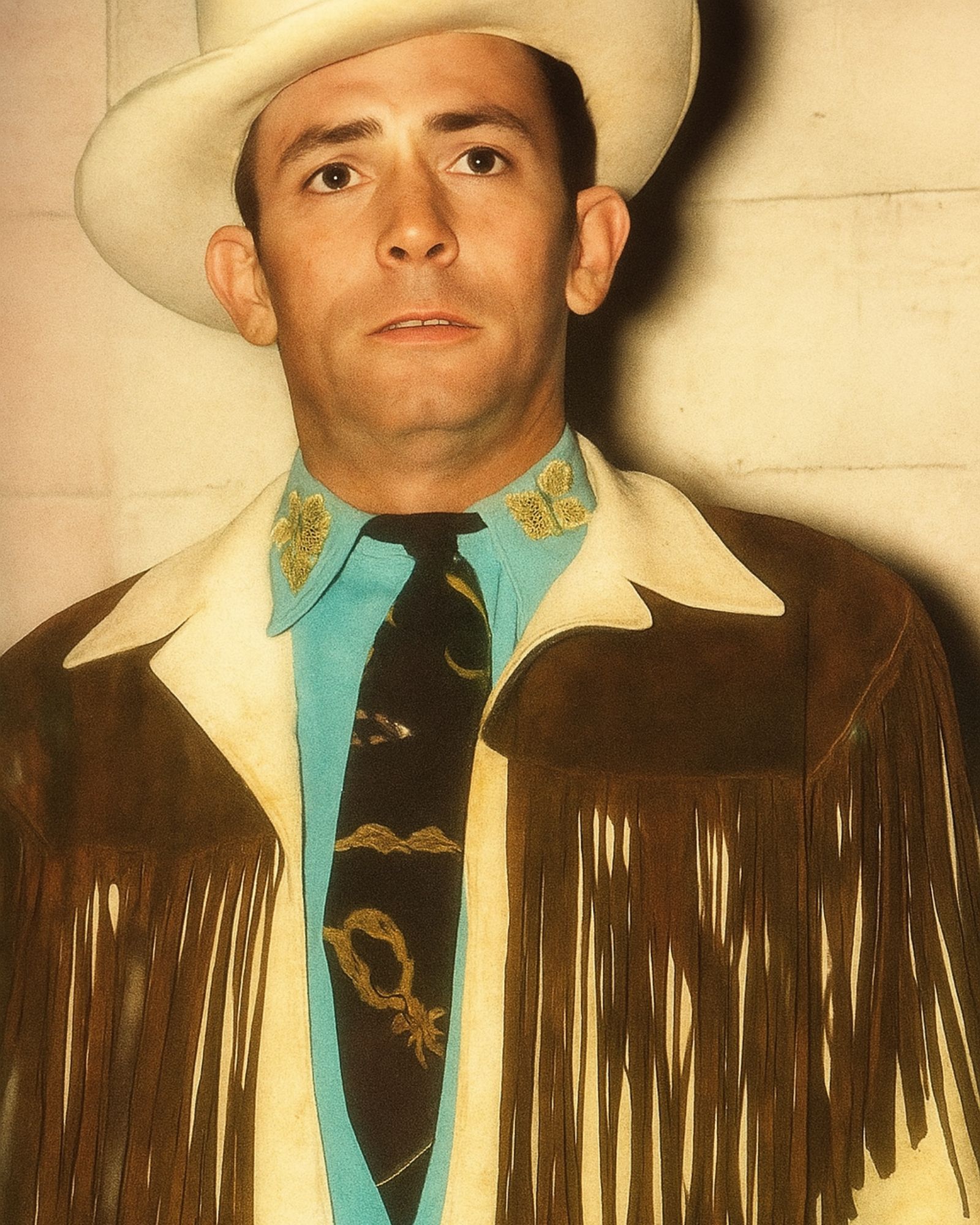

And he was right. The world understood. When Hank sang that song, hat tilted low and eyes half-closed, it wasn’t just country music — it was confession wrapped in steel guitar. It was every man who’d ever been left, every woman who’d ever walked away.

That night in 1950 didn’t just give birth to a song. It birthed a truth: that pain, when turned into poetry, can heal more than it breaks.

And as long as hearts still get cold, Hank’s will keep on burning — one verse at a time.