He Sang It Once. Then He Came Back and Slowed It Down — And It Changed Everything

The Song That Rode in Like a Gunman

When Marty Robbins first recorded “El Paso” in 1959, it didn’t feel like a country song. It felt like a movie in motion. A young outlaw, a jealous rival, a desperate ride back to the woman he loved — all packed into four fast-moving minutes.

The tempo was brisk. The guitar galloped. Marty’s voice carried confidence, almost bravado. Radio stations couldn’t get enough of it. The song shot to No. 1, and suddenly Marty Robbins wasn’t just a singer anymore — he was a storyteller with a stage big enough for legends.

Audiences loved the drama. They loved the ending. They loved the outlaw who paid for love with his life.

But at the time, Marty sang it like a role.

Not like a memory.

Years Passed. The Story Stayed.

Life did what life always does.

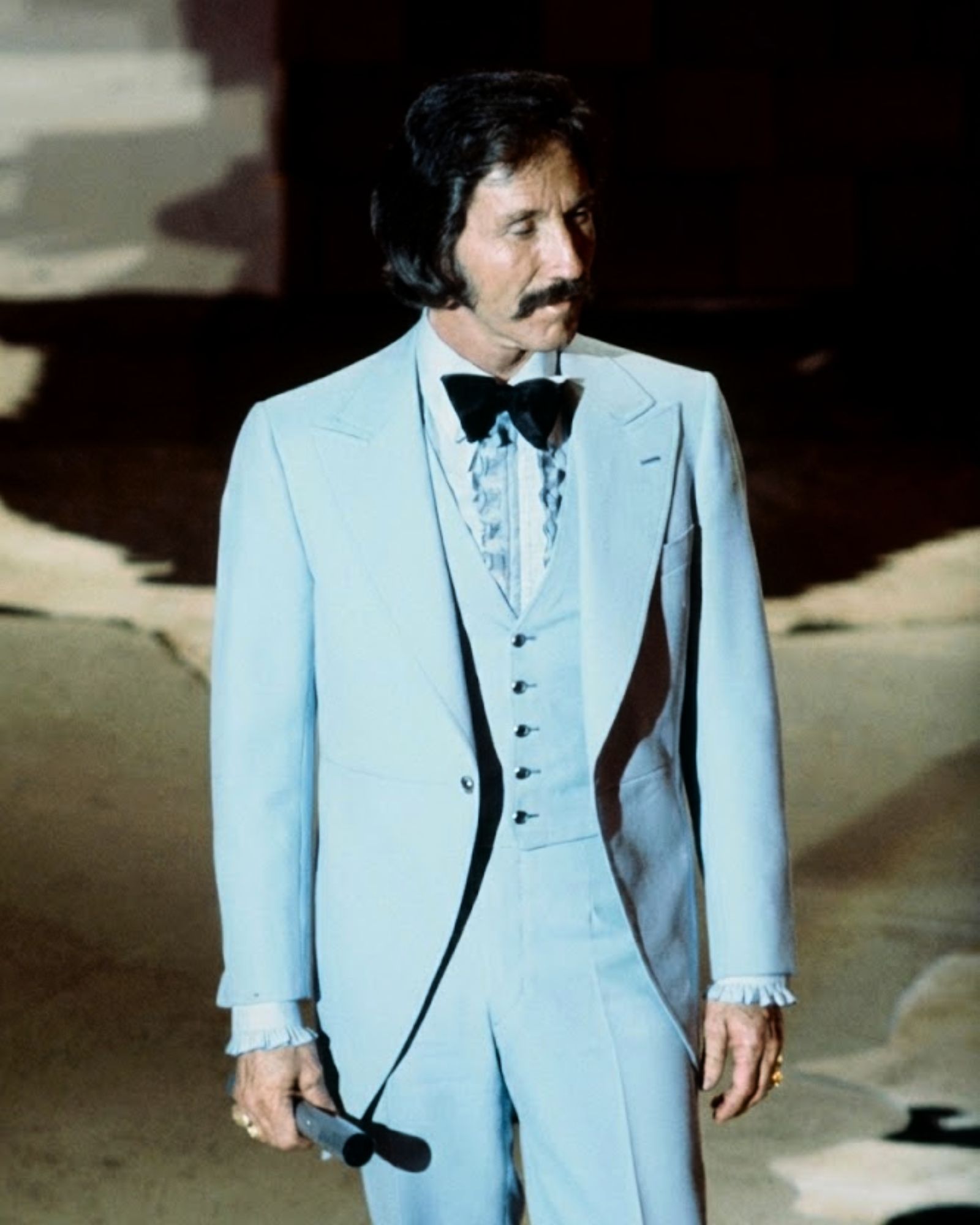

Tours blurred together. The spotlight faded and returned again. Marty raced cars, battled health problems, and carried the quiet weight of years on the road. By the late 1970s, his voice had deepened, and his body no longer moved like it once had.

Friends said he began to look at “El Paso” differently.

Not as a hit.

Not as a script.

But as something unfinished.

He told a producer once, half-joking, “I think I finally know how that man felt.”

The Second Time Wasn’t for the Charts

When Marty decided to revisit “El Paso,” it wasn’t announced as a comeback. There were no press releases. No radio push. Just a quiet studio session with a smaller group of musicians.

He asked for the lights to be turned down.

He asked for fewer people in the room.

And then he asked for something no one expected:

“Slow it down.”

The famous gallop became a walk.

The swagger softened.

Each lyric landed heavier than before.

Where the first version sounded like a tale told around a campfire, this one sounded like a confession whispered into the dark.

Not an Outlaw Anymore — A Man

The musicians noticed it immediately.

He didn’t rush the lines about jealousy.

He lingered on the ride back to El Paso.

And when he reached the final verse, his voice didn’t rise.

It settled.

One engineer later said it felt like Marty wasn’t singing about the outlaw anymore.

He was standing beside him.

When the last note faded, Marty didn’t remove his headphones.

He didn’t crack a joke.

He didn’t ask for another take.

He stayed in his chair, hat still on, eyes down, hands resting in his lap.

No one spoke.

The Silence After the Song

They say the room stayed quiet for a long moment — long enough to feel uncomfortable. Long enough to feel respectful. Long enough to understand that whatever had just happened wasn’t technical.

It was personal.

That slower version of “El Paso” never replaced the original. The hit still belonged to the fast ride and the young outlaw. But this version belonged to something else entirely.

It belonged to a man who had lived long enough to understand regret.

To understand longing.

To understand what it means to go back, even when you know how the story ends.

What Changed Wasn’t the Song

“El Paso” was always about love and loss.

But time taught Marty Robbins what those words really meant.

The first recording told a story.

The second one carried a life.

And somewhere between those two versions, a Western ballad became something deeper — not just a legend of the desert, but a mirror held up to the man who sang it.

Whatever Marty heard in that slower take wasn’t the outlaw’s voice anymore.

It was his own.